|

| "The Great I Am" by Gerald Roulette "This depiction is that you need to know when (Jesus) is looking at you, He is saying ‘I died for you because I love you. Anything you’re going through, I’ve got your back’ ... If you look at those eyes, He’s looking at you, letting you know, ‘I have your back’.” |

+ Gerald Roulette

discussing

In honor of Black History month, I want to provide you with an overview of how often God's story in the Bible has involved and been shaped by our black and brown sisters and brothers of color who looked to Jesus and found Him looking back at them with His eyes saying "I died for you because I love you. Anything you're going through, I've got your back."

The center of early Christianity was in the Middle East and North Africa. ... So historically, the claim that Christianity is European is fundamentally false. It is a fact hiding in plain sight that the three major centers of early Christianity were Rome, Antioch, and Alexandria. Alexandria is located in Egypt, a major early center of African culture. We do not have firm information on how Christianity came to North Africa, but tradition has it that it was evangelized by St. Mark. From this North African church comes some of the greatest minds that Christianity has produced, such as Augustine and Tertullian (as well as some of its first most bold and beautiful martyrs, like Perpetua and Felicity in the Passion of Saints Perpetua and Felicitas, the most substantial example of writing by a Christian woman in the first three centuries after Jesus' life, death, resurrection, and ascension).

The leading lights of early Christianity were Black and Brown folks or Egypt isn't as African as we say it is. We cannot have a pan-African account of history in which all Black and Brown people count as African in the secular account, but not the Christian one. Stated differently, if some secularists can look back to the greatness of our African past as the basis for Black identity now, then Black Christians (and all Christians of every ethnicity) can look to early African Christianity as their own.

+ Esau McCaulley, Reading While Black, pg. 97

"Black Identity in the Story of God"

adapted from excerpts in

African American Biblical Interpretation

as an Exercise in Hope

by Anglican priest Esau McCaulley

adapted from excerpts in

African American Biblical Interpretation

as an Exercise in Hope

by Anglican priest Esau McCaulley

An Exercise in Hope

Creation

All of humanity was created to be in God's life-giving and overflowing presence, and earth was created to be the realm where God dwelt with His creation. Humanity was with God, not only to reflect God's image, fashioned and loved in all of the Creator's beauty and wonder, but also to share His eternal goodness, reign, justice, and righteousness with each other and all of creation (Genesis 1:27-28; see The Story of God's Justice). With God, everything was very good for humanity and creation, full of potential, diversity, equity, and life, worthy of the Creator and Giver of life (Genesis 1:31).

All of humanity was created to be in God's life-giving and overflowing presence, and earth was created to be the realm where God dwelt with His creation. Humanity was with God, not only to reflect God's image, fashioned and loved in all of the Creator's beauty and wonder, but also to share His eternal goodness, reign, justice, and righteousness with each other and all of creation (Genesis 1:27-28; see The Story of God's Justice). With God, everything was very good for humanity and creation, full of potential, diversity, equity, and life, worthy of the Creator and Giver of life (Genesis 1:31).

Crisis

But the first humans came to a point when they wondered, "Is being made in God's image the best way to relate to each other and the world?" They settled for less than God's partnership, usurped God's good and bountiful plans, and broke fellowship to try to rule without the Creator and King's unique creativity, equity, justice, and goodness to all the world. Being made in the image of a beautiful and wonderful God was disrupted by mistrust, fear, darkness, and evil. Separation, violence, skepticism, and grasping to fill the void spread everywhere across peoples and places, stoking the fires of prejudice, hierarchy, isolation, and dread of the other (Genesis 6:5-6, 11-12). Humanity didn't want to cultivate the creativity and diversity of God's world, and instead tried to huddle together in one place, building a hierarchy of power for their own name in a tower that was Babylonia (i.e. place of confusion; see Genesis 11:1-8).

But the first humans came to a point when they wondered, "Is being made in God's image the best way to relate to each other and the world?" They settled for less than God's partnership, usurped God's good and bountiful plans, and broke fellowship to try to rule without the Creator and King's unique creativity, equity, justice, and goodness to all the world. Being made in the image of a beautiful and wonderful God was disrupted by mistrust, fear, darkness, and evil. Separation, violence, skepticism, and grasping to fill the void spread everywhere across peoples and places, stoking the fires of prejudice, hierarchy, isolation, and dread of the other (Genesis 6:5-6, 11-12). Humanity didn't want to cultivate the creativity and diversity of God's world, and instead tried to huddle together in one place, building a hierarchy of power for their own name in a tower that was Babylonia (i.e. place of confusion; see Genesis 11:1-8).

Covenant Community

After an increasingly destructive and violent period of time, God's response was to call a barren couple, Abra(h)am and Sarai(h), and miraculously birth a nation from them to bless all peoples, nations, and ethnicities of the earth (Genesis 12:1-3). The Abrahamic blessing is relevant to Black identity because it shows that God's vision for His people was never limited to one ethnic group, culture, or nation. His plan was to bless the world through Abraham's descendants. Therefore, from the beginning God's vision included Black and Brown people.

After an increasingly destructive and violent period of time, God's response was to call a barren couple, Abra(h)am and Sarai(h), and miraculously birth a nation from them to bless all peoples, nations, and ethnicities of the earth (Genesis 12:1-3). The Abrahamic blessing is relevant to Black identity because it shows that God's vision for His people was never limited to one ethnic group, culture, or nation. His plan was to bless the world through Abraham's descendants. Therefore, from the beginning God's vision included Black and Brown people.

(And, on another important note, Hagar, the first person to name God, El Roi, "The God who sees me" in Scripture in Genesis 16:13, honoring the God of Abraham even when Abraham and Sarah dishonored her, was a female African slave, another instance where the Bible elevates someone and God remembers Hagar who would often be forgotten in Ancient Near East culture.)

Insomuch as Christianity takes its bearing from the Old Testament, the global nature of Abraham's vision proves lie to any claim that the Messiah Jesus, the ultimate heir of Abraham (Matthew 1:1; Galatians 3:16), belongs only to Europe. The importance of Africans fulfilling the Abrahamic promises can be seen in the story of Jacob, Ephraim, and Manasseh. Black Christians will be familiar with the story of Joseph, who was enslaved and sold by his brothers to Egypt. Eventually Joseph rose in power, ending up second only to Pharaoh. Pharaoh also gave Joseph an Egyptian wife, Asenath, by whom he had two sons, Ephraim and Manasseh (Genesis 41:41-52). After the dramatic reconciliation between Joseph and his brothers, the family is reunited and takes up residence in Egypt. Toward the end of Jacob's life, Joseph brings his two boys to be blessed by his father. Meeting these two half-Egyptian, half-Jewish boys causes Jacob to recall the promise that God made him many years prior (Genesis 48:3-5). Jacob sees the Brown flesh and African origin of these boys as the beginning of God's fulfillment of His promise to make Jacob a community of different nations and ethnicities, and for that reason he claims these two boys as his own. These boys become two of the twelve tribes of Israel. Egypt and Africa are not outside of God's people; African blood flows into Israel from the beginning as a fulfillment of the promise made to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. As it relates to the twelve tribes, then, there was never a biologically "pure" Israel. Israel was always multiethnic and multinational as God's covenant family. And when God liberates the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob from slavery, these Israelites were portrayed as having African blood.

And what of God's covenant community who left Egypt after a long period of slavery? Exodus 12:38 says that "a mixed crowd" went up with them. A better translation of Exodus 12:38 would be that a large number of different ethnic groups came out of Egypt. Given that we know that Cush (Nubia) had relations with Egypt it is not that big of a stretch to believe that some of those who left Egypt were Black and that there were other Middle Eastern folks who departed with the Israelites.

We also know that Moses himself married a black African woman, Zipporah, who was approved of by God. We learn in the Book of Numbers in the Torah that Moses married this strong Cushite woman because Miriam (and Aaron) spoke against him in light of his marriage (Numbers 12:1). A "Cushite" is a way to label someone who came from the region of Cush south of Ethiopia, where the people are known for their dark skin. Cush was the name given to the area south of Egypt where African people blessed and cultivated God's earth, multiplied in number, and flourished for millenia. And in response to Miriam’s criticism of Moses' Black, African, Cushite wife (whether because Moses married above or below his station as Zipporah was the daughter of a priest), God disagrees with Miriam's critique ... and temporarily gives her leprosy (until Moses graciously asks for her healing). Why? Consider this lyrical justice. In God’s just displeasure with Miriam, God is saying to her and any other Israelite who looks at her dark color of skin in a displeasing way, “Do you think your light skin is better, Miriam? ... Leprosy is a shade lighter, but we know you don't think that shade is better.” God approves of Moses marrying a Black African Cushite woman, and we see this all the more through His discipline of Miriam when she critiques her brother's choice of an African wife. Black is beautiful to God in Scripture.

This diverse gathering of Black and Brown bodies newly liberated from slavery (and even from Moses' own family line with his Cushite wife, Zipporah, and with his great-nephew, Phinehas, the biracial priest whose name translates to the "Nubian," or "the Cushite" and whose father, Eleazar – one of Aaron the High Priest's sons – married a daughter of the Egyptian Putiel) is directly connected to God's promise to Abraham that He would make him the father of many nations.

Given the strong link between the story of Abraham and ethnic diversity, the link between the Abrahamic promises and the Davidic promises take on special significance. Psalm 72 presents itself as one of the final prayers ever written by David (it concludes with "the prayers of David son of Jesse are concluded"). What hope does David have for his son (Solomon) and how are these hopes connected to the hopes of the Black and Brown bodies and souls that look for comfort in these texts? ... David prays that the government might be a place where justice flourishes, and the afflicted can turn to the most powerful person in the country for deliverance. This is not just good news for Israel. It is good news for the whole world. Psalm 72:8 continues, "May he rule from sea to sea / and from the River to the ends of the earth." This is an expansion of the promise God made to Abraham in Genesis 15:17-18. According to the psalmist, the promised offspring of Abraham is not simply entitled to the land of Israel, but the entire earth. The promises to Abraham, then, are fulfilled throughout the worldwide rule of the promised son of David. This is not a mere expansion of territory. It is an expansion of justice and concern for the afflicted (Psalm 72:1-4) as a fulfillment of the Abrahamic promises. We know that the Abrahamic promises inform his vision for his son because he evokes them later in the psalm when he says, "All nations will be blessed through him, and they will call him blessed." This is almost a direct quotation of Genesis 12:3 refocused around the son of David.

What do Abraham and David together mean for the Black and Brown bodies spread throughout the globe? It means that the vision of Hebrew Scriptures is one in which the worldwide rule of the Davidic king brings longed-for justice and righteousness to all people groups.

Christ

Given the fact that the future Davidic kingdom is depicted as just and multiethnic, it is important to remember the emphasis on Jesus' Davidic and Abrahamic sonship throughout the New Testament (Matthew 1:1; Mark 10:47; John 8:56; Romans 15:8, 12; Revelation 5:5). The early Christians seemed to agree that the Old Testament contained a vision for the conversion of the nations of the earth in the promises made to David and Abraham. They saw in Jesus and the mission that He gave to His followers the fulfillment of those promises. According to these Christians, Jesus is the manifestation of God's love for the ethnicities of the world. Texts such as Psalm 72 claim that when the Son of David takes the throne his rule will be marked by justice for all those nations under His dominion. The New Testament writers were convinced that His rule began with the resurrection of Jesus from the dead and that God had called them to announce this good news of Jesus' kingship to the world. It seems from the perspective of the New Testament writers that all the ethnic groups of the world are necessary for the story to reach its proper end. John's word to his congregation – "We declare to you what we have seen and heard so that you also may have fellowship with us; and truly our fellowship is with the Father and with His Son Jesus Christ. We are writing these things so that our joy may be complete" (1 John 1:3-4) – could be rewritten to say that:

The joyous fellowship of the people of God is incomplete without the ethnic groups He promised to include in His family. God's vision for His people is not for the elimination of ethnicity to form a colorblind uniformity of sanctified blindness. Instead God sees the creation of a community of different cultures united by faith in His Son as a manifestation of the expansive nature of His grace. This expansiveness is unfulfilled unless the differences are seen and celebrated, not as ends unto themselves, but as particular manifestations of the power of the Spirit to bring forth the same holiness among different peoples and cultures for the glory of God.

Church

The picture of discipleship that comes to define early Christianity is the image of taking up one's cross (Matthew 10:38; 16:24). And Simon of Cyrene was compelled to carry the cross (Matthew 27:32). Cyrene is a city in North Africa in what we now call Libya. Simon's cross carrying is a physical manifestation of the spiritual reality that Christian discipleship involves the embrace of suffering. Mark states that Simon is the father of Rufus and Alexander (Mark 15:21). Why mention these men? The most logical answer is that Rufus and Alexander were known to Mark's audience. If anyone was tempted to doubt the veracity of Mark's account of the crucifixion, they could ask Rufus and Alexander, living members of the Christian community. We cannot say for sure when or how, but at some point this African father became convinced of the truth of the Gospel and passed that faith to his sons and possibly his wife (Romans 16:13). At the moment in which Christ is reconciling the world to Himself on the cross, an African family is making its first steps toward the Kingdom.

The family of Simon the Cyrene are not the only African believers in the early Church. Philip was directed to encounter an Ethiopian eunuch in charge of the treasury for the queen mother of Ethiopia (Acts 8:26-39). Within the narrative world of Acts, the conversion of this Ethiopian manifests God's concern for the nations of the world. Philip approaches him and discovers that he is reading a passage from Isaiah. The Ethiopian could only be familiar with Isaiah if he already knew something of the God of Israel. This shows a deep African connection to the God of the Bible. The passage he was reading from Isaiah is Isaiah 53:7-8 (see Acts 8:32-33). This text is an enigma to the Ethiopian, so he asks Philip to explain it. We are not told what Philip says. We do know that Isaiah 52:13-53:12, which recounts the fate of the suffering servant, was a central text in early Christian interpretation of Jesus' death (Galatians 1:4; 2:20; Romans 4:25; 8:32). In its Old Testament context, the servant narrative of Isaiah 53 is preceded by the announcement of a new exodus in Isaiah 52:11-12. But the question remains, How can this liberation that Isaiah foresees occur? The answer is the servant of Isaiah 53. He is the one who was "despised and rejected" but nonetheless "bore our suffering" and was "pierced for our transgressions." The early Christians interpreted Isaiah 53 as a reference to Jesus whose death for sins reconciles Israel and the world to God. When we combine the account of Simon with that of the Ethiopian eunuch we find that two Africans are brought to the Christian faith by means of powerful encounters with the cross. This story of Jesus crucified and risen drew the Ethiopian in and led him to be baptized. Again, this shows clearly that Africans are drawn to Christianity in much the same way as everyone else. Christ died for our sins to reconcile us to God.

I also find significance in the fact that the Ethiopian eunuch was reading from a particular portion of the servant's narrative, namely the portion where it says that justice was denied him (Isaiah 53:8). The eunuch was not materially poor, but as one who had been castrated he was in a socially ambiguous position because eunuchs were often despised. In a culture with strictly defined gender roles, he would be seen as aberrant. Is it possible that he felt that what had been done to him was a grave injustice – for which he was forced, for his own safety, to keep silent like the silently suffering Christ? Was there a point of connection between the rejection the servant experienced and the rejection that the eunuch experienced? If the eunuch did connect with Jesus as the one who suffered injustice, then he would be the starting point of an unending stream of Black believers who found their own dignity and self-worth through the dignity and power that Christ received at His resurrection. Maybe the eunuch's conversion is an example of the inversion spoken of by Paul in 1 Corinthians 1:26-29. This eunuch as a "despised thing" found hope in the shamed Messiah whose resurrection lifts those with imposed indignities to places of honor. This indignity was not ontological. The eunuch remained an image bearer. Christ showed the eunuch who he truly was. Christ, similarly, does not convey worth on ontologically inferior blackness.

Those of African descent are image bearers in the same way as anyone else. What Christ does is liberate us to become what we are truly meant to be, redeemed and transformed citizens of the Kingdom. What do the stories of Simon and the Ethiopian eunuch mean for Black Christianity? They show that the story of early Christianity is in part our story. We are at the cross. We are at the beginning of the emerging Christian community.

Christianity is ultimately a story about God and His purposes. That is good news. God has always intended to gather a diverse group of people to worship Him.

(New) Creation

Revelation 7:9-10 looks to the end, and at the end we encounter ethnic diversity. The reference to multitude calls to mind the promises made to Abraham that he would become the father of many nations. It also evokes the promises made to David that his son would gather and bless the nations of the world by his gracious rule. John mentions four aspects of this multitude: persons from every nation, tribe, people, and language. Each in its own way highlights diversity. These distinct peoples, cultures, and languages are eschatological, everlasting. At the end, we do not find the elimination of difference. Instead the very diversity of cultures is a manifestation of God's glory.

God's eschatological vision for the reconciliation of all things in His Son requires my blackness and my neighbor's Latina (or Asian Pacific, African, Caucasian, etc.) identity to endure forever. Colorblindness is sub-biblical and falls short of the glory of God. What is it that unites this diversity? It is not culture assimilation, but the fact that we worship the Lamb. This means that the gifts that our cultures have are not ends in themselves. Our distinctive cultures represent the means by which we give honor to God. He is honored through the diversity of tongues singing the same song. Therefore inasmuch as I modulate my blackness or neglect my culture, I am placing limits on the gifts that God has given me to offer to His Church and Kingdom. The vision of the Kingdom is incomplete without Black and Brown persons worshiping alongside white persons as part of one Kingdom under the rule of one King.

|

| “Pantocrator (which means 'Ruler of the Universe') in Black and Brown,” mixed media, by Brian Behm from Chapel Hill, N.C. |

Summary of Creation, Crisis,

Covenant Community, Christ, and

(New) Creation

Covenant Community, Christ, and

(New) Creation

There are two groups that want to separate African Americans from the Christian story. One group claims that Christianity is fundamentally a white religion. This is simply historically false. The center of early Christianity was in the Middle East and North Africa. But deeper than the historical question is the biblical one. Who owns the Christian story as it is recorded in the texts that make up the canon? I have contended that Christianity is ultimately a story about God and His purposes. That is good news. God has always intended to gather a diverse group of people to worship Him. The energy of the biblical story after the fall (i.e. crisis) finds its footing in the promises made to Abraham that he would be the father of many nations. In the stories of Ephraim and Manasseh, we see that this promise was first fulfilled by bringing two African boys into the people of God. We see the inclusion of Africans again reiterated when a multiethnic group of people left Egypt. These promises to Abraham were expanded into a kingdom vision through the hopes of a Davidic king who would rule and bless the nations. The repeated claim of the New Testament is that Jesus is the King who brings these promises to fulfillment. He gathers the nations under Him. We see this vision become flesh throughout the conversion of Africans: Simon and his family as well as the Ethiopian eunuch.

Just as at the origin of the Israelites, at the origin of Jesus' Church we find Black and Brown believers. Finally, we see at the end, when we finally meet our Savior, we do not come to Him as a faceless horde but as transformed believers from every tribe, tongue, and nation.

When the Black Christian enters the community of faith, she is not entering a strange land. She is finding her way home.

+ Esau McCaulley,

Reading While Black,

pgs. 116-117

Bonus Poem

He never spoke a word to me,

And yet He called my name;

He never gave a sign to me,

And yet I knew and came.

At first I said, "I will not bear

His cross upon my back;

He only seeks to place it there

Because my skin is black."

But He was dying for a dream,

And He was very meek,

And in His eyes there shone a gleam

Men journey far to seek.

It was Himself my pity bought;

I did for Christ alone

What all of Rome could not have wrought

With bruise of lash or stone.

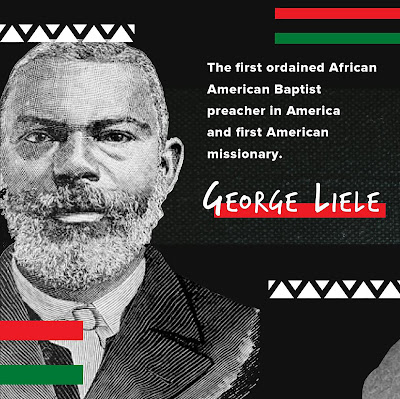

He was the first Baptist missionary

from the United States

And as far as I can tell

he was not only the first,

but the only missionary

to sell himself into slavery

to free others of their eternal slavery.

Think of that:

How convinced

do you have to be of the Gospel,

to sell yourself into slavery?

And how sobering and sad the cost Liele had to pay to be obedient to the call of God.

+ Bryan Loritts

+ Countee Cullen

1903 –1946

Bonus Story

What do you do if you are a slave who has recently secured freedom for yourself and family, but feels called by God to preach the Gospel in another country where slavery is also legal, yet you don't have the money to get there? If it's me, I'm going to act like I didn't hear God and head north.

But if it's George Liele (1750-1828), he's going to pay the cost of his trip to Jamaica, with the understanding between he and his master that once he pays off his debt he and his family are free. So off to Jamaica George goes, preaching the Gospel, planting a church and seeing many come to Christ. When Liele dies, there will be more than 20,000 believers in Jamaica, with most being able to trace their conversion either directly or indirectly to him.

The legacy of George Liele

is that of the first.

First African American

to be ordained as a Baptist preacher.

is that of the first.

First African American

to be ordained as a Baptist preacher.

He was the first Baptist missionary

from the United States

(not Adoniram Judson).

And as far as I can tell

he was not only the first,

but the only missionary

to sell himself into slavery

to free others of their eternal slavery.

Think of that:

How convinced

do you have to be of the Gospel,

to sell yourself into slavery?

And how sobering and sad the cost Liele had to pay to be obedient to the call of God.

+ Bryan Loritts

Bonus Black History Month Posts

+ Sojourner Truth, True Ezer-Warrior

+ Come Taste Grace w/ Langston Hughes

+ John Henry Disney Short Film Script

+ OCS: Absalom Jones, Free

+ OCS: Harriet Tubman, Visionary

Bonus Post

Yeshua | More Can Be Mended

May God's Kingdom come, His will be done.

Que le Royaume de Dieu vienne,

que sa volonté soit faite.

愿神的国降临,愿神的旨意成就。

Nguyện xin Nước Chúa đến, ý Ngài được nên.

Jesús nuestra Rey, venga Tu reino!

🙏💗🍞🍷👑🌅🌇

With wild grace and holy shalom,

Rev. Mike "Sully" Sullivan

No comments:

Post a Comment